The Feminization of the Church, by Sister Kaye Ashe (1997)

Posted in Books by Sinsinawa Dominicans

Sister Kaye Ashe, Prioress General of the Sinsinawa Dominicans from 1986-1994, issues a strident call in her 1997 book The Feminization of the Church? for “affirmative action” to “feminize” the Catholic Church by changing meanings and practices. This was published by the National Catholic Reporter, an organization that is afoul of canon law in numerous ways, according to their local bishop. This book is an inside look at how radical feminist heretics think. It proposes socialism and Marxism as corrective to traditional ethics, suggests female friendship as the ideal model of all relationships among created beings, and approves of Catholic women who make up their own all-women liturgies instead of going to Mass. This book is, in short, absurd, chilling, post-Catholic and anti-Catholic.

The book includes a forward by heresiarchess Sister Joan Chittister, in which Sister Joan speaks approvingly of mothers who “edit” their children’s catechesis, as part of mounting “a clear and confident contradiction of canons and practices and moral instructions based on the inferiority of women, the inequality of the sexes, and the invisibility of women in the church. They debate such subjects in the presence of their children.” Sister Joan explains: “That kind of catechesis builds another church in the shell of the old one.” That doesn’t bother Sister Joan: “It is a new church, whether anyone wants it to be new or not.” She sees Sister Kaye’s book as sounding the alarm that the Church needs to accept feminism as the way to “wholeness,” or else become “redundant.”

Sister Kaye cites an article by Christine E. Gudorf (who states in her 1995 book Body, Sex and Pleasure, that “the entire approach of Christian sexual ethics has been and is grievously flawed….ignorance which has allowed and supported patriarchy, misogyny, and heterosexism, the assumption that heterosexuality is normative”) to suggest that “the church lost public status and credibility in the political realm when it protested the scientific discoveries and the rule of the scientific method that began in the 16th century” leading to the Church being seen as domestic and private–“feminine”. Vatican II sought to move the Church back to the public sphere, Kaye says, and explains:

It is my intention in this book to examine further the potential of feminist analysis to bring the church and its members to greater wholeness. I will not, as Gudorf does, look upon feminist theory as a means of recovery from the church’s “feminization.” I will see it rather as a means of effecting the feminization of the Church understood as the full inclusion of women in the life of the church.

Women have, of course, always been fully included in the life of the Church, but as we shall see, what she means is the full inclusion of women in the priesthood and wielding power.

She begins by defining spirituality as now having to do with “self-fulfillment” and “consciousness”, without reference to growth in holiness, and immediately moves on to critique of great classic spiritual books as promoting a masculine spirituality which women (according to her) cannot relate to. She mocks the Desert Fathers’ “futile attempts to rid themselves of sexual fantasies” and references critique of the ascetical practices of the desert monks in the feminist screed Pure Lust by Mary Daly, about which see Janet Smith’s critique on the website of the Archdiocese of Detroit. Kaye astonishingly dismisses the women penitents who left a sinful way of life and “adopted unquestioningly and with enthusiasm the extreme asceticism that was the desert ideal” as having not “significantly influenced the spirituality of the monks.” I’ve read the book she cites, Harlots of the Desert, and it in fact emphasizes how powerfully inspiring these women were to monks. But Kaye’s disappointment seems to be that they didn’t reject penance and asceticism. Then she lays into The Imitation of Christ, which to her is horrible for saying that “[s]elf-knowledge leads to seeing oneself as mean and abject, indeed as a despicable worm” (she doesn’t mention, Sinsinawa Dominican founder Samuel Mazzuchelli’s personal copy resides in the congregation’s museum). The Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius has similar flaws, she says, and she doesn’t like that it tells us the body and self are to be conquered. I wondered if Kaye had an alternate plan for or alternate way of speaking of overcoming lust, sloth, gluttony, pride, etc, but suspected all this was her way of saying that resisting sin was no longer essential to “spirituality.”

Sister Kaye likes Julian of Norwich quite well and sees her as saying sin ultimately has no reality, and she approves of Sor Juana Inez de la Cruz, yet disapproves of her ultimately giving up her writing career in obedience to ecclesiastical authorities. Dorothy Day is “both an ally and a critic” of feminists. One of the contemporary sources Kaye likes is the non-Catholic feminist journal Woman of Power, and she prints its statement of women’s spirituality “for conscious evolution of our world,” which includes such new-age notions as “the activation of spiritual and psychic powers” and “the honoring of women’s divinity.”

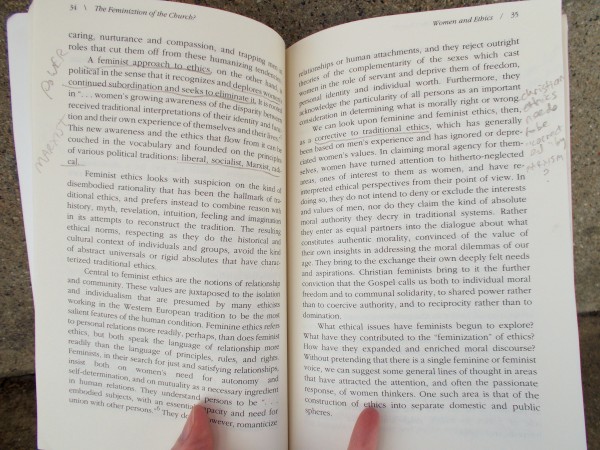

Chapter 2 is on “Women and Ethics”. “So profound are the questions raised” by women’s spirituality, says Sister Kaye, “that Margaret Farley wrote 20 years ago of the beginnings of a moral revolution.” Farley’s 2006 book Just Love, which the New York Times says “attempted to present a theological rationale for same-sex relationships, masturbation and remarriage after divorce” was condemned by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith last year,–so, immediately the informed reader’s attention is drawn back to the undermining of Catholic teaching on sexual morality. Kaye laments what she claims to be “[w]omen’s exclusion from the human task of discerning what constitutes moral behavior.” “A feminist approach to ethics… deplores women’s continued subordination and seeks to eliminate it…. This new awareness and the ethics that flow from it can be couched in the vocabulary and founded on the principles of various political traditions: liberal, socialist, Marxist, radical.” She seems untroubled by this, in fact after elaborating a bit she says this on the next page: “[w]e can look upon feminine and feminist ethics, then, as a corrective to traditional ethics.”

Let me put together for you what Kaye seems to be proposing: “liberal, socialist, Marxist, radical…. as a corrective to traditional ethics.” Here is the page, so you can decide for yourself whether I am telling you straight:

The critique of Christianity continues: “Feminists are suspicious of the concept of total self-sacrifice as being at the heart of Christian love, particularly when the notion is applied primarily to women in the home.” Since in Christianity this notion is always, always applied in the first place to Jesus’ self-sacrifice on the Cross, and Saint Paul says husbands are to love their wives as Christ loved the Church (ie, totally self-sacrificially), I do not see where she is coming from. This applies to all Christians and I have never seen it presented as being “primarily” about women in the home.

Sister Kaye’s line of thought takes an even more disturbing turn when she introduces us to Dorothy Sölle, who, bizarrely, “suggests that ‘phantasy’ rather than obedience is at the center of the Christian ethical system.” Hmm. No.

Kaye moves on to how women have “sought control over their own bodies, especially in the area of reproductive rights.” People scarcely question now whether the Pill is moral, Kaye says, though abortion is more complex. She asserts that “more and more Catholics who accept the Church’s teaching on the morality of abortion, nevertheless favor its legalization. Sr. Ivone Gebara, a gifted Brazilian theologian who was recently silenced by Vatican authorities, declared in an October 1993 interview for Veja that abortion should be a mother’s choice and should be legalized.” As I write this, it was not even an hour ago that I was with a friend who shed tears in sorrow over having aborted her baby boy years before. “I’m starting to become pro life,” she said. And I never met anyone with a more vivid tale of how contraception had harmed her health and made men feel they had license to exploit her. Speaking as a younger laywoman, these sisters gravely misunderstand the reality, and they make me angry. Furthermore, Sister Kaye does not promote marriage or chastity as being good, and those things actually are good. Kaye simply wants “full recognition of women’s sexual rights, which does not preclude a profound respect for motherhood.” I want so much for Sister Kaye to know, women do not need a “right” to fornicate and abort. This only harms us, as way too many of us know from experience.

This chapter finishes up with Mary Hunt’s (founder of the radical feminist dissent group Women’s Alliance for Theology Ethics and Ritual) proposal of “female friendship… as a model for relationship among all the elements of God’s creation.” How far does she care to take this? “Female friendship can, furthermore, serve as a model for male-female friendship, and for male-male friendship….”

Chapter 3 on “Women and Language” promotes of course the ideological feminist warping of English, even of Scripture texts and liturgy. This quite frankly includes editing the meaning of Scripture to fit feminist sensibilities: “removing the androcentric bias of scripture texts–a worthy and necessary task.”

Sister Kaye claims bizarrely that “women’s absence in liturgical language effectively excluded them from full participation in the life of the Church.” Was Saint Catherine of Siena effectively excluded from full participation? Kaye is upset that inclusive-language edits to the Eucharistic Prayers were not approved, and consequently “disaffected worshipping communities began to make their own textual changes, and… women continued to abandon corporate worship.”

Some women are creating “feminist liturgies” that “ritualize relationships that emancipate and empower women” and “critique patriarchal liturgies.” “Instead of receiving a blessing from a specially ordained man, the women present are likely to bless one other.” Sometimes, in fact, they do this kind of thing instead of going to Mass: “If, in order to speak and pray authentically, they must congregate in all-women assemblies, they will continue to do that.” But it’s a sin to do this instead of Sunday Mass, you say? Kaye says the feminist-liturgy women should “gain confidence in their own perspective on what it means to be sinful.”

Chapter 4, “Women and Ministry” of course winds its way around to the topic of women and the priesthood. Blessed John Paul II’s Apostolic Letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, which declared infallibly that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women, “stunned, saddened and enraged countless Catholics” like Sister Kaye, who then in turn attacked the meaning of infallibility. She claims that “many respectable scholars… insist that a male-only priesthood is a matter of church order or discipline and, as such, cannot be made a matter of faith, much less an infallible teaching.” Although doubtless there are scholars who think that, their opinion is opposed to unchangeable Catholic teaching, and is not a “Catholic” opinion. From a faithfully Catholic perspective, such scholars are simply wrong, and this is an idea with terrible consequences for the communion of the Church, as sadly we’ve seen locally.

Remarkably, Kaye Ashe does not ignore or shy away from the fact that “women’s ordination” breaks the communion of the Church, but describes two points of view of women’s ordination advocates: those who believe ordination of women is compatible with the nature of priesthood in the Catholic Church and that change is possible, and those who acknowledge that feminist goals are not reconcilable with the nature of priesthood in the Catholic Church and “that women’s energy should be spent on creating a different kind of ministry in a different kind of church.” She cites lesbian feminist theologian Mary Hunt of the radical feminist dissent group WATER, as “a Catholic theologian who is in full sympathy with those who have lost patience for the patriarchal trappings of the church” and feels the best strategy for “the women-church movement” is to let the “anti-ordination” and “pro-ordination” “positions” “co-exist in mutual critique,” in other words to foster confusion and indifferentism, as the teaching authority of the Church is denied and truths of the Faith are downgraded to the status of issue positions to be debated based on secular feminist criteria.

Another thing I notice in Sister Kaye’s discussion of ordination, is an omission: she does not present it as a Sacrament. She cites a Dominican friar I heard give an extraordinarily theologically dodgy talk at the Sinsinawa-sponsored Edgewood College earlier this year, Fr. Thomas O’Meara, who wants to define ordination liturgies “not as a liturgical exercise of episcopal power, not as something bestowed by juridical decree, but as a ‘… communal liturgy of public commissioning to a specific ministry.'” And as if to make it quite unambiguous she doesn’t approach priestly ordination as being a Sacrament, Kaye says, “And can we hope someday to arrive at a theology of ministry in which distinctions between lay ministry and clerical ministry, ordained and non-ordained ministry, will be meaningless?” Martin Luther and his followers had pretty much the same “hope” and consequently they do not have most of the Sacraments. As Catholics, no we cannot and must not hope for such a thing, since the distinction between who is a validly ordained priest and who is not has an absolute importance: only a validly ordained priest can celebrate Mass and validly consecrate the Eucharist. Realizing that most if not all “women’s ordination” supporters have a very different idea of what priesthood and ordination mean to them (and consequently different beliefs about the Eucharist), than what it is in the Catholic faith, is essential to understanding their movement, its non-Catholic or anti-Catholic nature, and how destructive it is to ecclesial communion.

The final chapter is on Women and Leadership, which makes it plain that the goal is power, a word Sister Kaye uses repeatedly. This is spiritual bankruptcy from a Christian perspective, but makes complete sense from Sister Kaye’s Marxist-feminist perspective. Women are supposed to keep fighting for “public power” in civil society, and women religious must continue moving “from positions of dependence and docile compliance, to the kind of autonomy and rightful use of power that characterizes healthy adults.” Then she makes some veiled allusions to situations experienced by her own Sinsinawa Dominican congregation, for instance in revising the Constitutions governing their way of life:

Gradually through resistance, dialogue and compromise in terms of language, if ont principle, congregations won approval of their reconceived and rewritten constitutions, and in the process succeeded in realigning themselves in relation to church authorities. The whole experience raised the question in many American congregations of the value of canonical status, and of the need to win the approval of men of another mindset and culture for the documents that embody the traditions and values that rule their lives.

In other words, they questioned whether they actually wanted to be a Catholic religious congregation anymore. There is also an account of the 1984 New York Times ad signed by many laity and also 24 women religious (among whom was Sinsinawa Dominican Sister Donna Quinn, who is not mentioned by name in the book), “stating that a diversity of opinion existed in the Catholic Church in regards to abortion.” Kaye clearly supported this, and adds something that was certainly true of Sister Donna: when the sisters and their religious congregations were required by the Holy See to indicate their adherence to Catholic teaching on abortion, “Many felt that the statements they signed or that the statements presented to Rome by their religious superiors did not constitute a retraction of what was stated in the ad, but Vatican officials interpreted the statements as such and cleared all but two of the signers,” namely Barbara Ferraro and Patricia Hussey, who Sister Kaye claims are still Catholic and “now frankly pro-choice though not pro-abortion.” Then Sister Kaye tells of a Planned Parenthood who was excommunicated, and some Call to Action members who were excommunicated; Sister Kaye strongly disagrees with that. She speaks positively of the pro-abortion-rights organization Catholics for a Free Choice.

After her discussion of “women’s ordination” in the previous chapter that seemed not to treat ordination as sacramental, I was surprised to see her write this: “Protestant churches have opened the ranks of the ordained to women, giving them the right to preach and teach, and to share in the sacramental power that is granted with ordination….” On the next page, she writes of an Episcopalian lady “bishop” who was sent by a male Episcopalian “bishop” “to celebrate Mass” at a conservative Episcopalian church where she received an icy reception. I am under the impression that the use of the word “Mass” is not very typical of liberal Episcopalianism, so this seems to be Kaye’s own choice, making me wonder if she considers the Episcopalian service to be “Mass.” Again, the confusion about the Sacraments reflected in this book is extreme. Catholics don’t consider Episcopalian ordination to be sacramentally valid.

Is the choice for Catholic women really between siding with the radical feminist “Women-Church Convergence” and its feminist theology and feminist liturgies, vs being “self-sacrificing victims, destined to abort their growth to full personhood in the interest of helping the men in their lives attain theirs”? Are women really to place their hope in “the uses of disorder in creating new possibilities for growth”? Fractals are beautiful, right, so making chaos in the Church and being “patient with ambiguity” might be right right way forward for the common good of womankind? Sister Kaye Ashe would have us consider that.

In her conclusion, Sister Kaye pulls it all together by explaining that the tool that’s shaping the process of the feminizing transformation of consciousness in the Church “is what Mary Fainsod Katzenstein has called ‘discursive politics,'” and quotes that author, who says this is “the politics of meaning-making. It is discursive in that it seeks to reinterpret, reformulate, rethink, and rewrite the norms and practices of society and the state….” Kaye states that “These, indeed, are the means that women in the church, and particularly feminists, are using. They are forging new meanings and constructing a new language to express their evolving understanding of themselves and of their relation to the church.”

If I understand her correctly, feminizing the Church means redefining Catholicism to be something fundamentally different. It is frankly political (even frankly Marxist) and involves radically changing what words mean, the way that the Sacraments are understood and practiced, the way we relate to Scripture, the way we understand basic human relationships, everything–it involves changing everything to enforce in everything the interchangeability of the sexes, and that the female sex is more equal than the other sex. Although it purports to do away with a Christianity based on obedience, in sum this project of “feminization” is absolutely tyrannical and I think of Pope Benedict’s phrase “the dictatorship of relativism.” Do you remember back in Chapter 1 when Kaye introduced us to the principle of “the honoring of women’s divinity”? It seems to me that that’s what, if we logically think through the ideas in Kaye’s book, now actually substitutes for God in this ideology.

An Appendix includes generally supportive short essay responses to various chapters by various Dominican leaders: Chapter 1, Donald J. Goergen, OP. Chapter 2, Daniel Syverstad, OP. Chapter 3, Edward M. Ruane, OP. Chapter 4, Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, OP. Chapter 5, Patricia Walter, OP. Blurbs on the back from Sister Anne Marie Mongoven, OP (Sinsinawa), Anne Carr, Univ of Chicago Professor of Theology, and Kate Dooley, OP (Sinsinawa).